Bill Graham howled. He talked. He shouted. He harangued. He laughed. He threatened. He barked. He sang (a little!)…Bill was one of the great mavericks who redefined what freedom really meant in the U.S.A.

– Pete Townshend

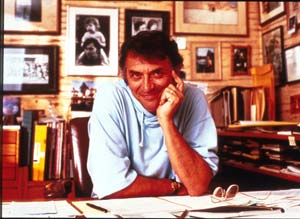

Creative and combative, charming and charismatic, Bill Graham was a child of history whose entire life was shaped by his family background. The son of Russian Jews who had emigrated to Germany in search of a better life, he was born Wolfgang Grajonca in Berlin on January 8th, 1931. Two days later, his father, who worked as a civil engineer, died of a blood infection after having been injured in an industrial accident. To support her five daughters and newborn son, Bill’s mother began selling artificial flowers, costume jewelry, and women’s skirts in various markets in the city.

After Krystillnacht, “The Night of Breaking Glass” on November 8th, 1938 when Nazi storm troopers and German citizens destroyed seventy five hundred Jewish shops as well as more than two hundred synagogues, Bill’s mother placed him and his sister Tolla in a kinderheim or children’s home to protect them. Eight years old, Bill stood with a crowd of people who shouted “Sieg Heil!” as Adolph Hitler passed by in a car.

Along with his sister, Bill was then sent to a chateau in France where they both lived until Paris fell to the Nazis in 1941. Fleeing the oncoming German troops, a worker from the International Red Cross led sixty-four children from the chateau. Moving constantly with very little to eat, Bill and his sister rode on buses and trains, walked for hours, and slept at night by the side of the road in the rain. Weakened by malnutrition, thirteen year old Tolla soon developed pneumonia.

In Lyon, the International Red Cross Worker told Bill, who was then ten years old, that his sister had to stay behind in the hospital but would join them again once she recovered. Bill never saw Tolla again and she most likely died in the hospital. From Lyon, Bill and the other children walked to Marseilles. They all spent two months in a convent in Madrid before moving to Lisbon where they were put on an ocean liner that docked in Casablanca and Dakar before taking nineteen days to cross the Atlantic as it dodged German U-boats. Sleeping on deck, Bill survived on cookies and oranges.

Suffering from malnutrition and rickets, Bill arrived in New York on September 24th, 1941. Nearly eleven years old, he weighed fifty-five pounds. His only possessions were his yarmulke, a prayer book, and some photographs of his parents and sisters. Of the sixty-four children who had set off from the chateau in France three months earlier, eleven made it to America.

Although Bill would not learn of her fate until after World War II had ended, his mother had already been gassed to death on a train while being transported to Auschwitz, the Nazi concentration camp to which his sister Ester was then also sent. Fluent in German and French but unable to speak or understand a word of English, Bill was placed in an army barracks in upstate New York. Each weekend, couples who had been offered forty-eight dollars a month by the Jewish Foster Home Bureau to take in refugee children came to select who they wanted to take home with them.

In what he would later describe as the most painful experience of his life, Bill carefully cleaned himself up each weekend and then stood beside his tightly made bed as people he did not know judged him in a language he could not understand. The last of the eleven children with whom he had come to America to be selected, Bill spent nine weeks waiting before finally being chosen by a couple from The Bronx whose own son happened to be studying French at The Bronx High School of Science.

Although he soon mastered English with the help of his foster brother, Bill initially spoke with a thick German accent and so found himself fighting each day with schoolmates who thought he was Nazi. Becoming the ultimate New York City street kid, he sold baseball cards, played craps in the schoolyard, and worked as a delivery boy to pay his own keep. In classic immigrant fashion, he learned about America by going to the movies where the actor John Garfield became his great hero.

After graduating from DeWitt Clinton High School, Bill attended Brooklyn College. He spent his nights dancing the mambo at the Palladium on Fifty-Third Street and Broadway in Manhattan where, as a mirror ball revolved above the dance the floor, Latin band leaders like Machito, Tito Puente, and Tito Rodriguez played songs that went on for fifteen or twenty minutes as everyone danced in what Bill would later call “the eye of this wonderful storm.” When he won the Wednesday Night Dance contest at the Palladium some years later, Bill considered it one of his greatest accomplishments.

Eighteen years old but not yet an American citizen, Bill was drafted to fight in the Korean War. Because no one could pronounce “Grajonca” correctly, he had changed it to “Graham” by selecting his new last name from the phone book. Constitutionally unable to deal with authority of any kind, Bill hated the Army. As a forward observer in the 7th Infantry Division whose job it was to go out at night to pinpoint the enemy’s location, he was awarded the Bronze Star for valor and a Purple Heart and promoted to corporal only to be busted back down to private for refusing an order he believed would result in his certain death. After his foster mother died, he was granted a hardship discharge.

Having first worked as kitchen boy in the Catskill Mountains during the summer when he was fifteen years old, Bill became a bus boy and then a waiter at Grossinger’s and the Concord Hotel, the top of the line resorts in what was then known as “The Jewish Alps.” While running a lucrative nightly craps and poker game for gambling-obsessed guests at The Concord, Bill put his own job on the line by unionizing the dining room staff at the hotel.

Returning to the city, he worked as a waiter and a cab driver while living in Greenwich Village. With no real idea what he wanted to do with his life, Bill repeatedly hitchhiked and drove to California and back again before deciding to become an actor. After studying with Uta Hagen and Lee Strassberg, he was cast in a variety of small roles but soon drifted back out to California where he became the business manager for the San Francisco Mime Troupe, the cutting edge radical theatre company run by R.G. “Ronny” Davis in which Peter Coyote began his acting career.

After the Mime Troupe was busted for giving what authorities termed an “obscene” performance in Lafayette Park, Bill put on an appeal party on November 6th, 1965 to raise funds for their legal defense at which Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Sandy Bull, The Fugs, John Handy, Allen Ginsberg, and The Jefferson Airplane appeared. During what he would later call “by far the most significant evening of my life in the theater,” Bill watched in amazement as people who did not know one another walked into the party and began dancing with one another.

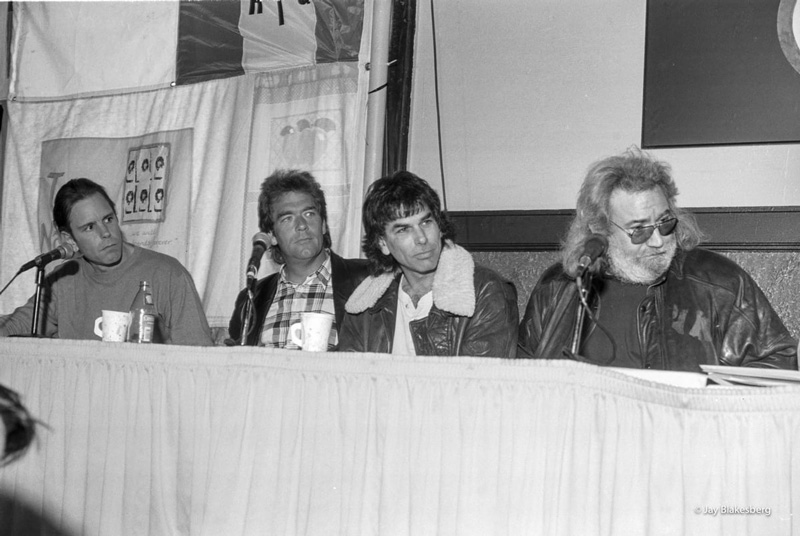

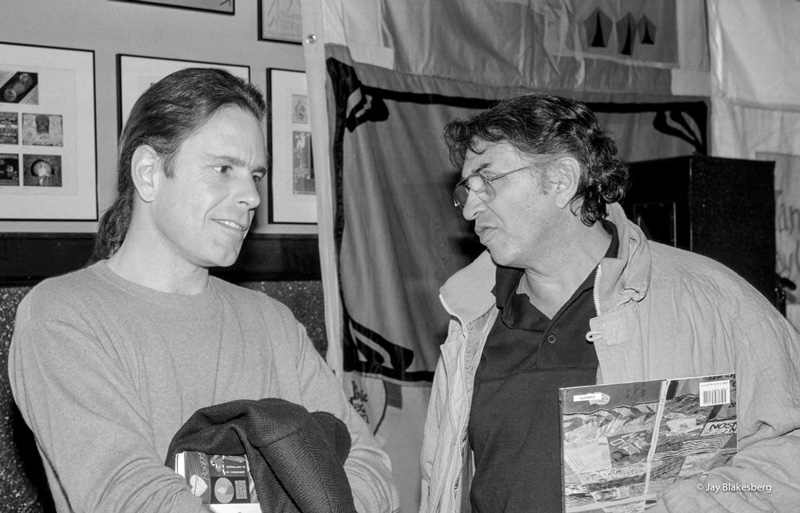

Having finally found something he was good at from which he could also earn a living, Bill put on a second benefit for the Mime Troupe at the Fillmore Auditorium but then parted ways with the theater group. After attending the Trips Festival at Longshoreman’s Hall where he had a memorable confrontation with Ken Kesey and began a lifelong friendship with Jerry Garcia by trying to put his shattered guitar back together so he could perform with The Grateful Dead, Bill began producing and promoting shows with Chet Helms of the Family Dog collective at the Fillmore. Their partnership did not last long and Bill began an epic series of battles to be allowed to continue presenting music for white kids in a black neighborhood.

At the Fillmore, Bill fought with the cop on the beat. He fought with the rabbi in the synagogue next door. With the backing of Charles Sullivan, the black entrepreneur whose dance permit he had been using to put on shows, Bill fought with the city council. All the while, he was putting on shows that featured Lenny Bruce opening for The Mothers of Invention, plays by LeRoi Jones (with The Byrds as headliners) and Michael McClure, and a reading by Russian poet Andrei Voznesensky and Lawrence Ferlinghetti at a Jefferson Airplane show. With a mirror ball revolving over the dance floor and the music playing at the Fillmore, Bill recreated the magic he had first experienced as teenager while dancing the mambo in the Palladium in Manhattan.

Asking the young white musicians who were creating the psychedelic sound who they wanted to see at the Fillmore, Bill began booking black artists who had never before played for white audiences. When Otis Redding performed for the first time at the Fillmore, Janis Joplin arrived at three in the afternoon to make certain she would be down front to see him. With The Grateful Dead, Quicksilver Messenger Service, Moby Grape, Big Brother and the Holding Company, the Butterfield Blues Band, and The Jefferson Airplane headlining, Bill brought great black artists like Freddie King, Albert King, B.B. King, Junior Wells, Lightning Hopkins, The Staple Singers, Chuck Berry, Howlin’ Wolf, and Muddy Waters to a brand new audience.

Bill brought The Doors and Jimi Hendrix to San Francisco for the first time. He also began booking English bands who had never before performed on the west coast. After The Who played for the first time in San Francisco for two nights at the Fillmore, they did their groundbreaking set at the Monterey Pop Festival. When Bill put on Cream for an unheard-of six nights, the group was forced to begin extending their songs because they did not have enough material to fill two sets and their extraordinary performances broke the band in America.

Right from the start, Bill saw the rock concert as theater and provided his musicians with the best sound and lights available. To advertise his shows, he had psychedelic artists like Wes Wilson, Rick Griffin, and Mouse and Kelley create landmark posters that have since become collectible art. Riding all over the city at night on his scooter, Bill put up the posters. He also created the first independent ticket distribution system by inveigling local head shops to sell tickets for him.

Completely hands-on, Bill booked the shows, took tickets at the front door, cleaned the bathrooms between sets, and put a barrel of apples by the entrance to the ballroom with a sign that read “Take One, or Two.” Working alongside his wife Bonnie Maclean, who did some of the earliest show posters, Bill made the Fillmore a safe haven where kids could experience the music they loved without getting busted. The Fillmore was Bill’s house. So long as you paid for a ticket, Bill treated you like an honored guest. And even when they drove him crazy, he treated his musicians like artists.

Bringing it all back home, Bill then expanded his operations by taking over a rundown former movie theatre on Second Avenue in New York City. The Fillmore East opened on March 18th, 1968 with Big Brother and the Holding Company supported by Albert King and Tim Buckley and soon became the premier venue for rock in the world. If a new band played a great set at Fillmore East on Friday night, the entire music business knew it by the next morning. In San Francisco, Bill began putting on shows in Winterland, a five thousand seat ice skating arena that was then the largest venue in which rock concerts had ever been regularly presented.

Moving into management, Bill guided the career of The Jefferson Airplane. With producer David Rubinson, Bill created two record labels, San Francisco Records and Wolfgang Records. He also founded FM Productions, which soon became the leading technical tour support company in rock. After discovering Carlos Santana, Bill engineered his meteoric rise to success by insisting the Santana Blues Band perform at the Woodstock Festival, an event put on in large part by those who had learned their craft from Bill at Fillmore East.

Now a media celebrity, Bill commuted between New York and San Francisco on a weekly basis. Completely consumed by his work, he saw his newborn son David for the first time when his photograph was shown on stage at Fillmore East. In New York City, Bill also collaborated with his idol, impresario Sol Hurok, to present rock for the first time at the Metropolitan Opera House. Burnt out by the stress of his never ending work schedule and the increasingly outrageous demands of superstar acts, Bill decided to close the Fillmores in 1971.

His retirement did not last long. Doing more shows than ever before at a variety of venues, Bill presented the Rolling Stones for two shows at Winterland as well as in Los Angeles, Long Beach, San Diego, and Tucson on their 1972 tour of America, thereby beginning his association with “the world’s greatest rock ‘n’ roll band.” A year later, Bill put on the first in what became a hugely popular series of one-day outdoor festivals known as “Day On The Green” at which Led Zeppelin, The Eagles, Fleetwood Mac, and The Grateful Dead and The Who (on a single bill) played before more than fifty thousand people at Oakland Stadium.

In 1974, Bill produced landmark arena rock tours by Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young, George Harrison, and Bob Dylan. A year later, Bill helped create the incredibly lucrative rock merchandising industry by funding Winterland Productions, the first purveyor of t-shirts for which musicians received royalties. When Bill learned a budget cut was about to put an end to all extracurricular activities in San Francisco public schools, he persuaded the city to let him put on a benefit he called SNACK – an acronym for “San Francisco Needs Athletics, Culture, and Kicks.”

On March 23rd, 1975, fifty thousand people filled Kezar Stadium to watch The Grateful Dead, Graham Central Station, Bob Dylan and the Band, Jefferson Starship, Tower of Power, the Doobie Brothers, Santana, Mimi Farina, and Neil Young perform. Featured speakers at the event included Marlon Brando, Joan Baez, and Willie Mays. The concert raised enough money to fund after-school programs in San Francisco schools for another year.

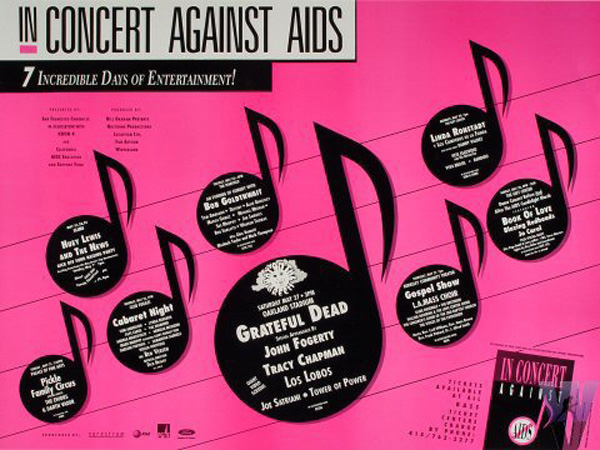

Although Bill had been doing benefits ever since he had first opened the Fillmore, SNACK was the first big rock benefit concert in history. By using the drawing power of artists who were willing to contribute their services for a worthy cause, Bill had discovered a way to use rock “to solve a social problem.” His willingness to invest his time and energy in projects from which neither he nor his company earned any money would in time make him the go-to guy in rock for anyone with a worthy cause.

In 1976, Bill put on The Last Waltz, the farewell concert by The Band and a

superstar supporting cast that was filmed by Martin Scorcese. With his marriage having long since ended in divorce, Bill began a long-term relationship with Marcia Sult who in 1977 gave birth to their son Alex in Hawaii. In 1981, Bill planned and managed the Rolling Stones massive stadium tour of America. The tour was a huge success and Bill then shepherded the Stones on their European tour the following year.

While managing artists like Carlos Santana, Van Morrison, Eddie Money, the Neville Brothers, Joe Satriani, and Blues Traveler, Bill returned to his first love and appeared as an actor in his good friend Francis Coppola’s Apocalypse Now, The Cotton Club, and Gardens of Stone. He also played the well-known Mafia boss, Charles “Lucky” Luciano in Bugsy, Barry Levinson’s film starring Warren Beatty

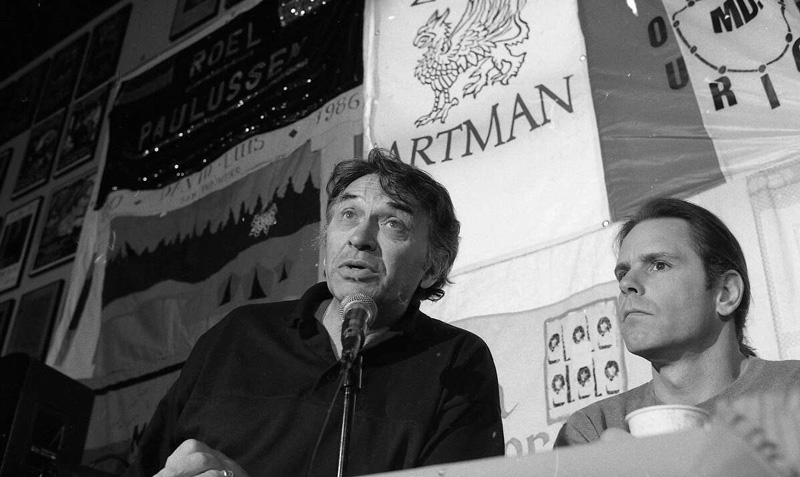

In 1985 after Bill had sponsored a rally in Union Square in San Francisco to protest President Ronald Reagan’s plan to visit a cemetery in Bitburg, Germany where members of the Waffen SS had been buried, the offices of Bill Graham Presents were firebombed and burned to the ground. A Holocaust survivor who had proudly lined the walls of his office with priceless rock memorabilia, Bill lost many of his most prized personal possessions in the blaze. Although those who set the fire were never caught, Bill and his company were soon back in business again.

After Bob Geldof came up with the idea of putting on a “Global Jukebox” with artists in both the U.S. and England performing on television all over the world to raise money to fight the devastating famine in Ethiopia, Bill produced the American Live Aid concert at the one hundred thousand seat John F. Kennedy Stadium in Philadelphia. The event, which raised more than forty-five million dollars to fight hunger in Africa, also proved that, as Bill would later say, rock had become “the international means of communication,” the single language everyone all over the world now understood. For his work on Live Aid, Bill was given MTV’s Lifetime Achievement Award.

Devoting his time and energy to charity projects no one else could have undertaken, Bill put together a six city “Conspiracy of Hope” tour in the summer of 1986 to celebrate the twenty-fifth anniversary of Amnesty International, the human rights organization dedicated to stopping violence against women, fighting to free prisoners of conscience, opposing torture, and defending refugees and migrants throughout the world. Featuring U2, The Police, Peter Gabriel, Lou Reed, Bryan Adams, the Neville Brothers, and Joan Baez, the tour raised $2.5 million for Amnesty USA and brought the organization a hundred and fifty thousand new members. The tour ended with a day-long concert at Giants Stadium in New York attended by sixty thousand people that was broadcast live by MTV.

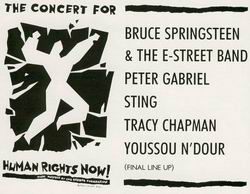

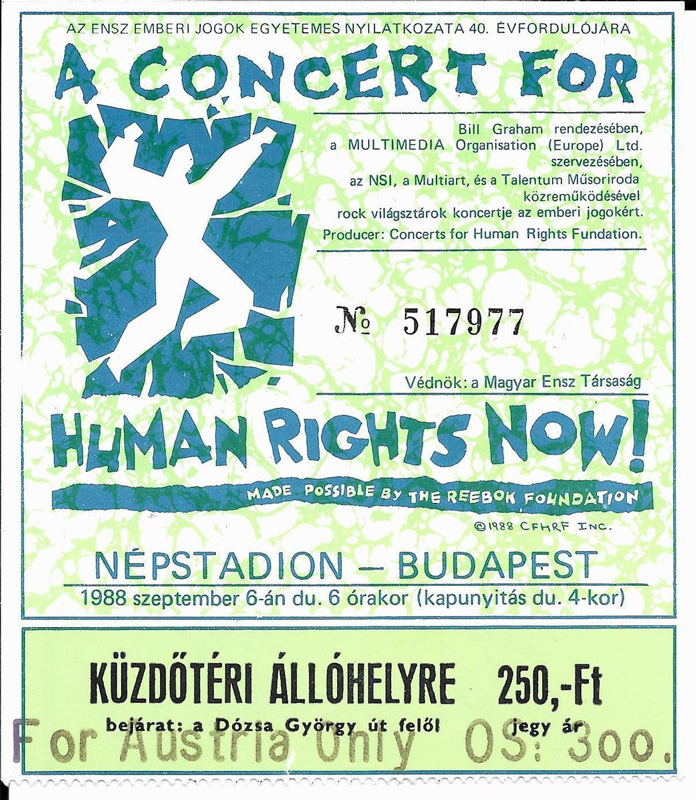

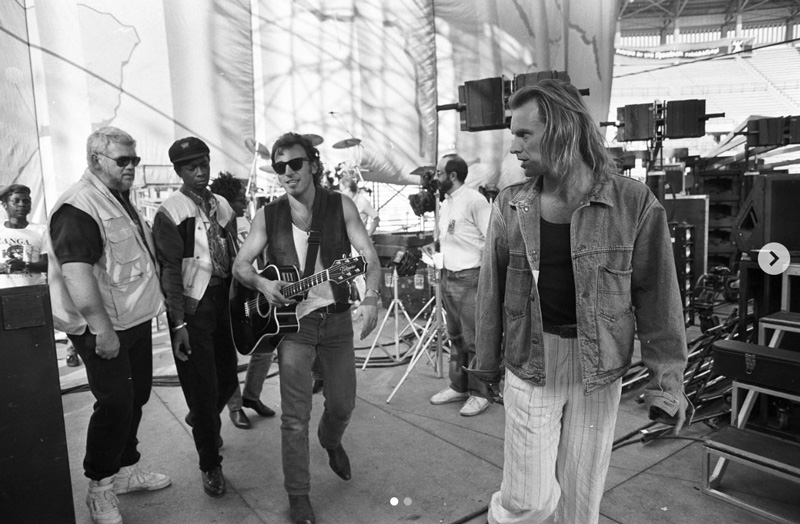

After presenting the first live stadium rock concert featuring American artists in Russia, Bill put together the “Human Rights Now!” tour in 1988 to celebrate the fortieth anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Featuring Yossou N’Dour, Tracy Chapman, Peter Gabriel, Sting, and Bruce Springsteen, the tour began in England and continued with concerts in Europe, Costa Rica, Canada, the United States, Japan, India, Zimbabwe, the Ivory Coast, Brazil, and Argentina. The sheer logistics of moving so many musicians around the world in “the greatest ever rock-music extravaganza” were staggering but the tour brought Amnesty’s message of hope to people in third world where the organization had long been struggling to achieve its goals.

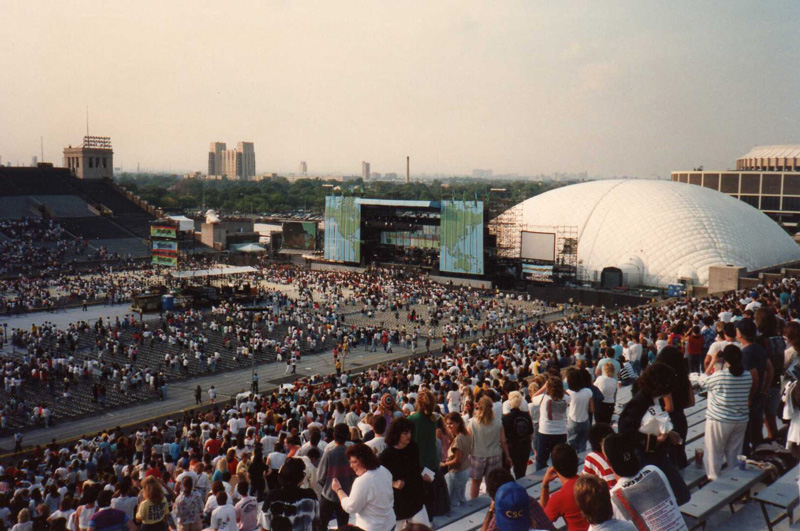

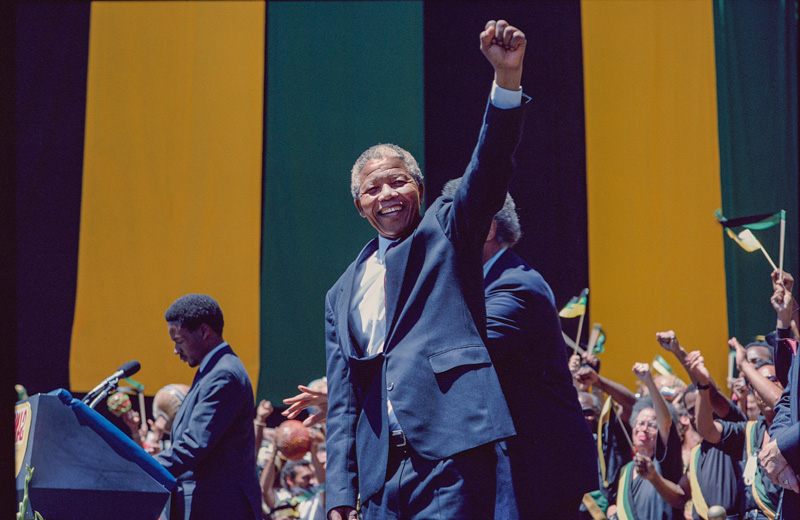

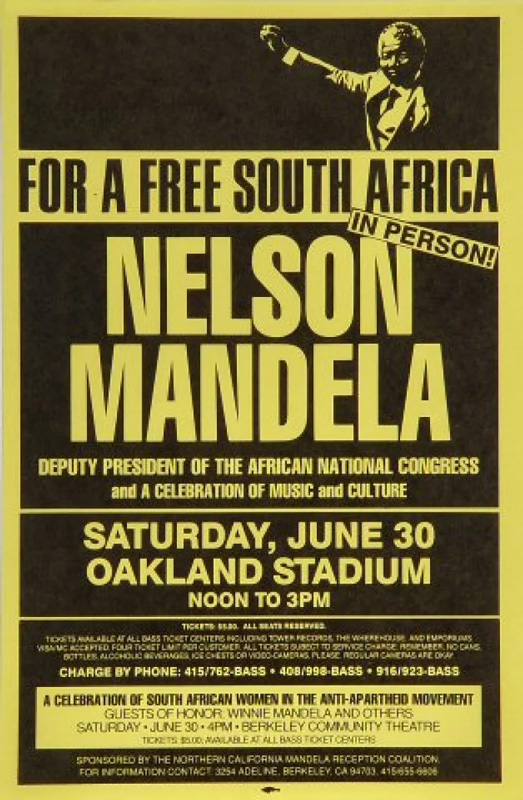

Despite his obsession to use rock as a force to raise consciousness throughout the world, Bill was still running a company with more than a hundred employees and he suffered a crippling personal breakdown when the Rolling Stones chose someone else to run their 1989 Steel Wheels Tour. As only he could, Bill managed to resurrect himself again and organized a twelve hour rock telethon that raised two million dollars for the victims of the massive earthquake that had struck the Bay Area in October, 1989. A year later, he brought sixty thousand people together in the Oakland Coliseum to welcome South Africa’s president, Nelson Mandela.

On Friday, October 25th, 1991, Bill was flying home from a Huey Lewis and the News show in the East Bay with his companion Melissa Gold when the helicopter piloted by his long time associate Steve “Killer” Kahn was caught in a sudden storm. Striking a power line, it exploded, killing all those on board. Sixty years old, Bill died as he had lived, doing what he loved best.

What may have been as many as half a million people filled the Polo Field in Golden Gate Park on November 3rd, 1991 at a free concert in Bill’s memory entitled “Laughter, Love, and Music.” Aaron Neville, Jackson Browne, Joe Satriani, Carlos Santana, Los Lobos, Robin Williams, Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young, John Fogerty, and The Grateful Dead performed. Joan Baez and Kris Kristofferson closed the show by singing “Amazing Grace.” Three months later, Bill was inducted posthumously into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

A one-of-a-kind human being who always seemed larger than life, Bill Graham was in the business of making people happy and never stopped trying to create what for him was the magical moment when the performer and the crowd came together and the music became a vehicle that took everyone to a higher plane. As much as anyone who ever lived, Bill Graham loved the music. He loved the money and the madness, much of which he helped bring to a business that since his passing has become increasingly corporate and impersonal.

For more than a quarter of a century, Bill Graham was the heart, the guts, the soul, and the conscience of rock. To the very end of his life, he continued to identify himself with those who had no real power in the world. Difficult as he could sometimes be, Bill always wanted to help. That the Bill Graham Foundation continues to do good works in his name is not just entirely fitting. As Bill might have said, it is also right.