Vergessenes Kind (Forgotten Child)

Berlin-based freelance journalist Cornelius Dieckmann visits the neighborhood where Bill was born 90 years ago and spent his early childhood. Some of his discoveries emerge in “Vergessenes Kind (Forgotten Child),” which appeared in the Frankfurter Allgemeine newspaper on Saturday, January 2, 2021.

See the article in German here. Below, find an English translation.

Forgotten child

As a rock impresario, Bill Graham wrote music history alongside Carlos Santana and the Grateful Dead, Janis Joplin and the Allman Brothers. The son of Russian Jews was born ninety years ago in Berlin. A search for clues.

By Cornelius Dieckmann

He was only known here as an American, and he probably had almost no memory of his childhood: In February 1956, William Graham, a prospective civil engineer in San Francisco, wrote a letter to the German state. Above it says: “Curriculum vitae (course of persecution).”

Further, in English: “I was born on January 8, 1931 in Berlin, Germany and was given the name Wolf (Wolfgang) Wolodia Grajonca. My father, who was a civil engineer, died shortly after I was born. I was the only son and the youngest of six children. My mother was not able to run her business and look after all the children at the same time.” She gave him as a little boy to a children’s home. In 1939, “when the widespread persecution of the Jewish people began,” he was taken to northern France on a train with other Jewish children.

The curriculum vitae, which can be found in Graham’s compensation file at the Berlin State Office for Civil and Regulatory Affairs, is accompanied by his last German certificate, issued in March 1939 by the first private boys’ primary school of the Jewish community in Berlin. In local history, Wolfgang Grajonca receives a three, in German only a four. He is better at arithmetic, where he can get a two, and gymnastics, a straight one. In music, the boy from the second grade, who will one day become the most important impresario in rock history, gets a two.

The curriculum vitae, which can be found in Graham’s compensation file at the Berlin State Office for Civil and Regulatory Affairs, is accompanied by his last German certificate, issued in March 1939 by the first private boys’ primary school of the Jewish community in Berlin. In local history, Wolfgang Grajonca receives a three, in German only a four. He is better at arithmetic, where he can get a two, and gymnastics, a straight one. In music, the boy from the second grade, who will one day become the most important impresario in rock history, gets a two.

After the Germans marched into Paris, Graham writes, he and the other children fled south on foot and were brought from Marseille via Madrid to Lisbon, “where we were accommodated on the Portuguese liner Serpa Pinto. After a stopover in Casablanca, we sailed across the Atlantic to Bermuda. We reached New York City on September 24, 1941.”

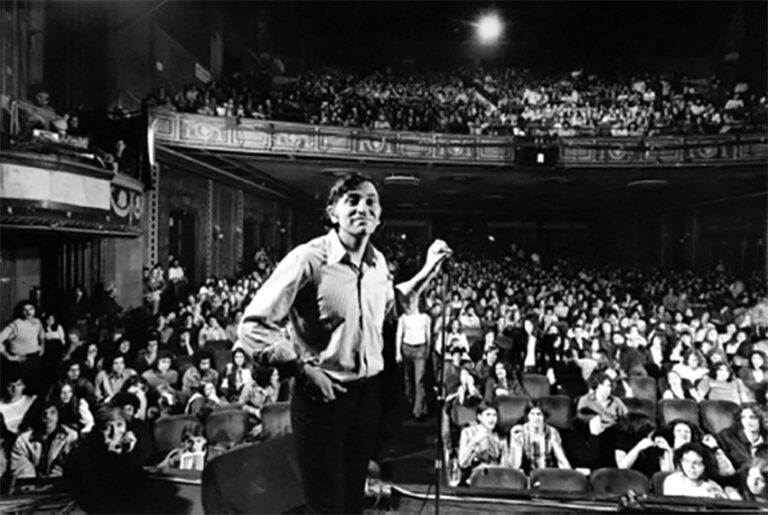

Graham lived in California in the mid-1960s. The Merry Pranksters celebrate their Acid Tests, the bands are called Jefferson Airplane and Quicksilver Messenger Service, the people are Mountain Girl and Wavy Gravy. The word “love” still works–soon an entire summer will be named after it. Bill Graham is ten years older than the hippies. Neon dreams are neither his life experience nor his temperament. His communication style will later be described by someone as “scream of consciousness.” But Graham realizes that ecstasy needs an organizer to keep the account books. He accepts that rock ’n’ roll plays against capitalism as well as within it.

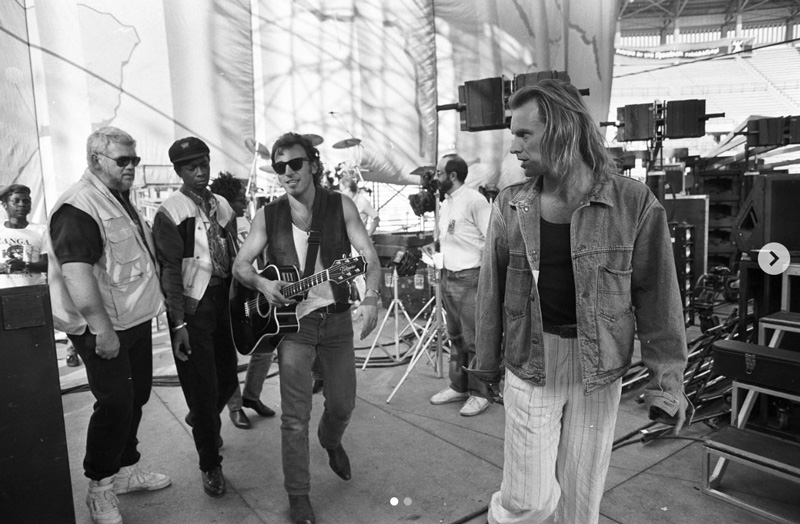

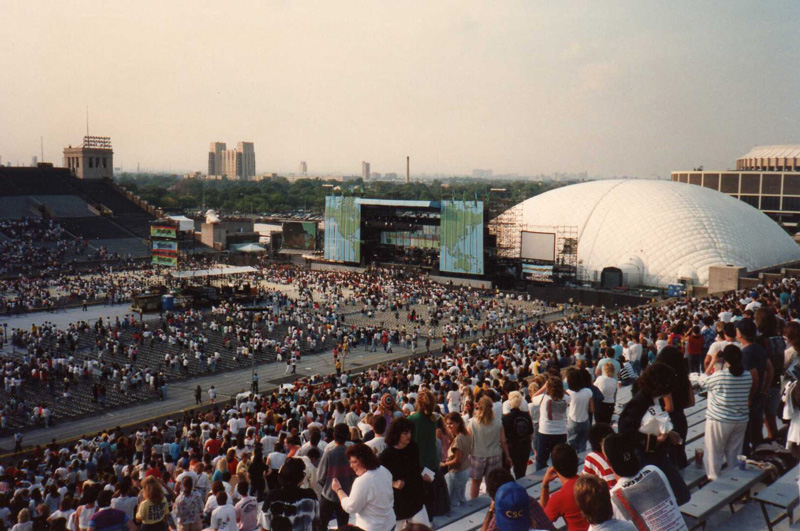

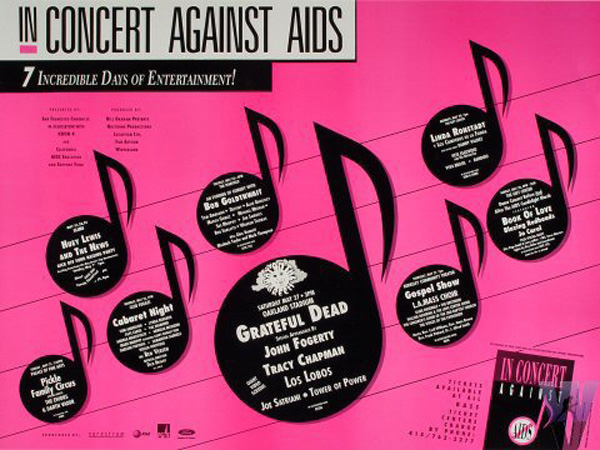

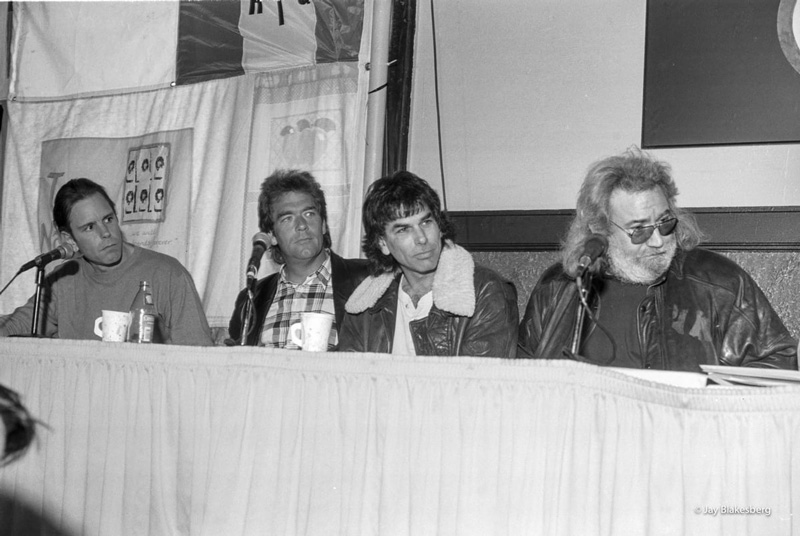

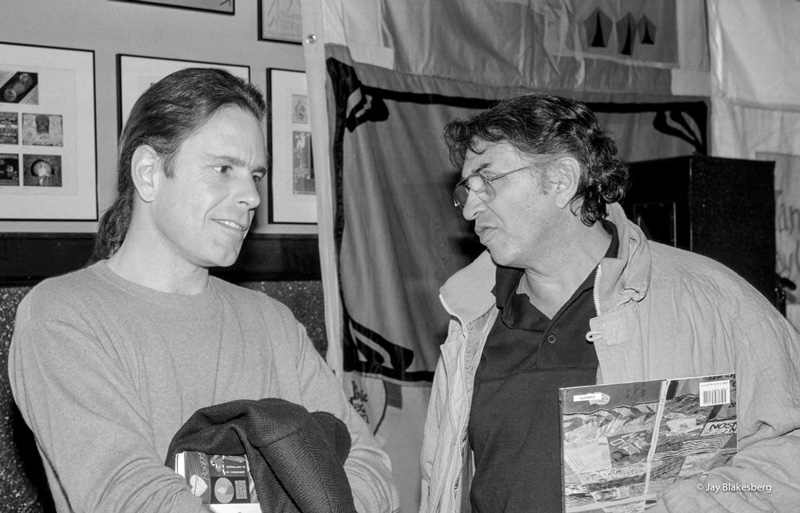

“When everyone was on LSD,” says Graham’s archivist James Olness, “Bill was the one who spoke to the police and said, these are my people. Without him there would have been many broken skulls.” Graham discovers Carlos Santana, he sabotages and protects Janis Joplin. He pairs the Grateful Dead with Miles Davis and shows Otis Redding and the Allman Brothers to the Northern California student rockers. Nearly 200 live albums are recorded at Graham’s Fillmore rock temples in San Francisco and New York from 1965 to 1971. In March 1971 alone, “Aretha Live at Fillmore West” and “At Fillmore East,” the record with which the Allman Brothers became famous, were created within a week. The concert posters always say: Bill Graham Presents.

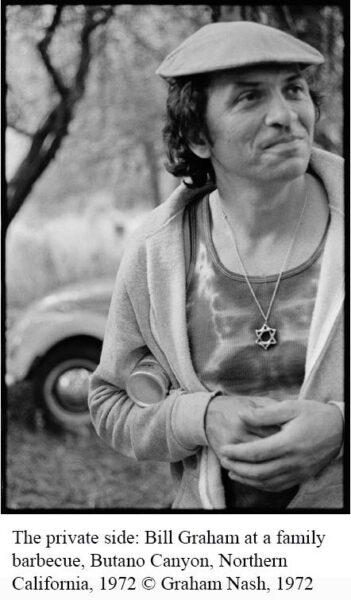

Bill Graham – he chose the common name to his later regret from a telephone book as an approach to Grajonca – was not the only Berlin Jew who fled Hitler’s Germany and wrote music history in America. Francis Wolff and Alfred Lion founded the epoch-making jazz label Blue Note in New York in 1939. But if there is the Alfred-Lion-Steg in Berlin, the German capital seems to have forgotten its son Bill Graham.

Graham was born in the Berlin University Women’s Clinic in the early afternoon of January 8, 1931. When the birth certificate for “Wolodia Wulf” was issued four days later, the father, Jacob, had already died as a result of an accident at work – two days after the birth. The mother, Frieda, has to feed Wolfgang, as one calls the boy, and his sisters Tolla, Ester, Sonja, Adele and Rita alone. The Grajoncas, bourgeois Jews of Russian origin, live at Lindenstrasse 36 in Kreuzberg. They love the theater and regularly go to the liberal synagogue on Lindenstrasse. Frieda studied harp at the conservatory in St. Petersburg, but the circumstances do not allow her to do artistic work. She sells artificial flowers and lingerie at markets, which earns her around 50 Reichsmarks a day.

In 1935 the family moved into a two-and-a-half-room apartment that was much too cramped at nearby Alte Jakobstrasse 8. It was their last voluntarily chosen address. The house was completely destroyed in the war. Today there is a Waldorf kindergarten on the property, next door accommodation for refugees, opposite the Berlinische Galerie. There is no Stolperstein [a commemorative plaque].

Yes, Jews also lived in their house, says Heinz-Eberhard Kuhn on the phone. Exactly, the Grajoncas. “They lived in the back side wing. They were very nice,” says Kuhn, born in 1935. The house in which he grew up belonged to his father, who spoke perfect Russian. “And my father, he had absolutely nothing against Jews.” At some point, recalls Kuhn, the Grajoncas were no longer there. “But well, as a child I didn’t notice that. My parents just told me that they moved.

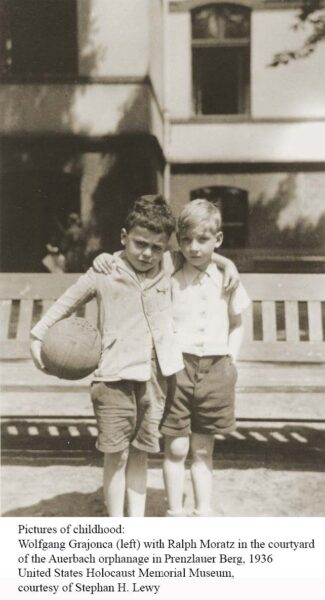

Schönhauser Allee 162, Berlin-Prenzlauer Berg. A place of remembrance for the Baruch-Auerbach orphanage. A granite football is attached to the sidewalk. In the bricks of the only wall that withstood the war bombs, the names and ages of the murdered are set, more than 150, the youngest only a year old.

A plaque shows photos from the Nazi era. Next to one it says: “Two little boys with a soccer ball.” It is Wolfgang Grajonca and his friend Ralph Moratz in 1936.

“Of course I knew him!” says Walter Frankenstein. He buried the photo himself between three trees in Grunewald “during the illegal period” and took it back in July 45! Or was it a fellow pupil who gave it to him after the war? Frankenstein no longer knows exactly. But he does remember the boy.

“Of course I knew him!” says Walter Frankenstein. He buried the photo himself between three trees in Grunewald “during the illegal period” and took it back in July 45! Or was it a fellow pupil who gave it to him after the war? Frankenstein no longer knows exactly. But he does remember the boy.

Frankenstein was born in 1924. From 1936 on, like Wolfgang, he lived in the Auerbach orphanage. He survived the war hiding in Berlin. The Jewish children’s home was “like an island in the brown sea,” says the 96-year-old on the phone from Stockholm.

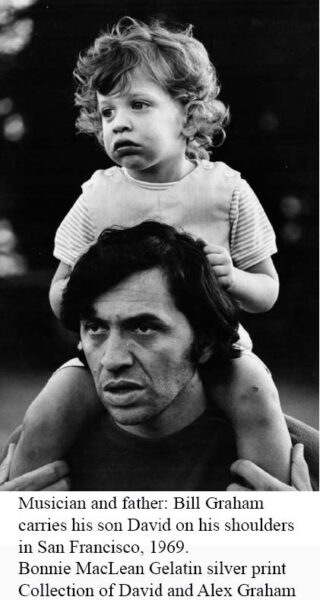

The pupils would have lived there like siblings. As an adult, Bill Graham was amazed that he could play several German melodies on the piano. Otherwise he has “total amnesia” in the first nine years of his life. Graham’s son Alex says that his father taught him “Cuckoo, cuckoo, call it from the woods” in the mid-1980s without being able to say how he knew the song. Was there any musical education in Auerbach?

“Yes, of course!” says Walter Frankenstein. “We had a grand piano in the dining room and you learned instruments. Every week we had a music evening, when the educator played Beethoven, Mozart, all the classics for us, with his comments. And then we also had a subscription to the Jewish Cultural Association. Jews were no longer allowed to go to the general theater or concerts, and so the Auerbach had a number of tickets that were always distributed to the children.” This is possibly how Bill Graham experienced his first concerts.

“You know, his teacher, that was Ilse Löwenstern,” says Frankenstein. “Miss Löwenstern to the little ones, that was like their mom.” It was thanks to her that the Auerbach did not burn down during the pogrom night of 1938.

On weekends, Wolfgang sleeps at home on Alte Jakobstrasse, on weekdays in Auerbach. November 9, 1938 is a Wednesday. Because the home director went into hiding, only 27-year-old Ilse Löwenstern is responsible for the children who are supposed to go to the in-house synagogue. When SA men wanted to set fire to the orphanage, Löwenstern and the older pupils were able to convince them that the fire would also spread to the neighboring houses.

“And then they left,” recalls Frankenstein, then 14. “But they had extinguished the flame of the eternal lamp in the prayer room and let the gas continue to flow out. And as soon as they were gone, we noticed: It smelled of gas. We went in there, opened the windows and turned off the gas tap.” The people of Auerbach quickly realize that the synagogues are burning all over Berlin. The Grajoncas’ synagogue on Lindenstrasse is also being devastated.

The National Socialists force Frieda Grajonca to give up her fabric trade. In February 1939, through the Aid Association of Jews in Germany, she asked for assistance in leaving for Shanghai, where her eldest daughter Rita emigrated. Frieda explains that she “speaks and write perfect German, Russian, Lithuanian, Polish, iwrith [Hebrew] and Yiddish. I am musical and a very good harpist.” She is also very versatile as a cook and seamstress. Answer from China: They are trying to get a “request letter” from local entrepreneurs, “but under no circumstances can we make firm promises. The G. family must act on their own responsibility and at their own discretion. We are sorry not to be able to give you anything more positive at the moment, but we fear the great responsibility for this family with the 5 young children.

Days before she received the final rejection in July, Frieda puts her two youngest children Wolfgang and Tolla on a Kindertransport. On July 3, 1939, the train leaves Potsdamer Bahnhof Berlin, destination Gare du Nord, Paris. “The sky was overcast with light rain that evening, which contributed to the eerie atmosphere that prevailed in Berlin in those years,” wrote Wolfgang’s childhood friend Ralph Moratz on his blog shortly before his death in 2016. “In the train station, a square on the platform was cordoned off where we were waiting for our train. (…) Around the ropes were the cruel SS and other armed soldiers who patrolled with growling dogs to make sure that we didn’t talk or touch our mothers and relatives. “

Days before she received the final rejection in July, Frieda puts her two youngest children Wolfgang and Tolla on a Kindertransport. On July 3, 1939, the train leaves Potsdamer Bahnhof Berlin, destination Gare du Nord, Paris. “The sky was overcast with light rain that evening, which contributed to the eerie atmosphere that prevailed in Berlin in those years,” wrote Wolfgang’s childhood friend Ralph Moratz on his blog shortly before his death in 2016. “In the train station, a square on the platform was cordoned off where we were waiting for our train. (…) Around the ropes were the cruel SS and other armed soldiers who patrolled with growling dogs to make sure that we didn’t talk or touch our mothers and relatives. “

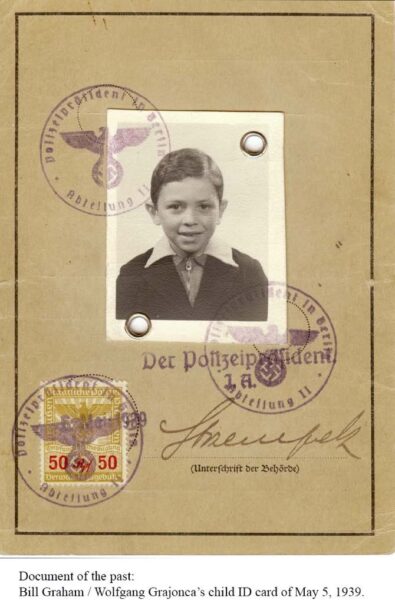

Wolfgang has his kippah, a prayer book and some family photos in his luggage, his papers are hung around his neck. “Wulf Israel” is shown as “stateless” on the child’s ID card that he carries with him. He did not become an American citizen until 1954. About forty children, half of them from the Auerbach, escaped on the Kindertransport. In order not to panic, they were told that they were going on vacation for two weeks. Wolfgang never sees his mother again.

Frieda Grajonca is picked up from her apartment on Alte Jakobstrasse on October 19, 1942 in the “21. Osttransport,” deported and probably shot in the woods near Riga. Among the 958 people abducted with her are 56 children from the Auerbach, all of whom the Nazis murdered. Wolfgang’s sister Tolla remains on the run to southern France and is brought back to Berlin. She was deported on December 14, 1942 and murdered soon after. The other four Grajonca sisters survive.

For the injustice suffered, including the “damage to life” of his mother and sister, Bill Graham is “compensated” by the Federal Republic and its states after several years of bureaucratic effort with 16,970 marks.

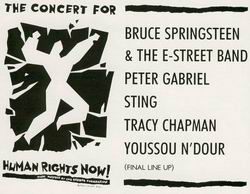

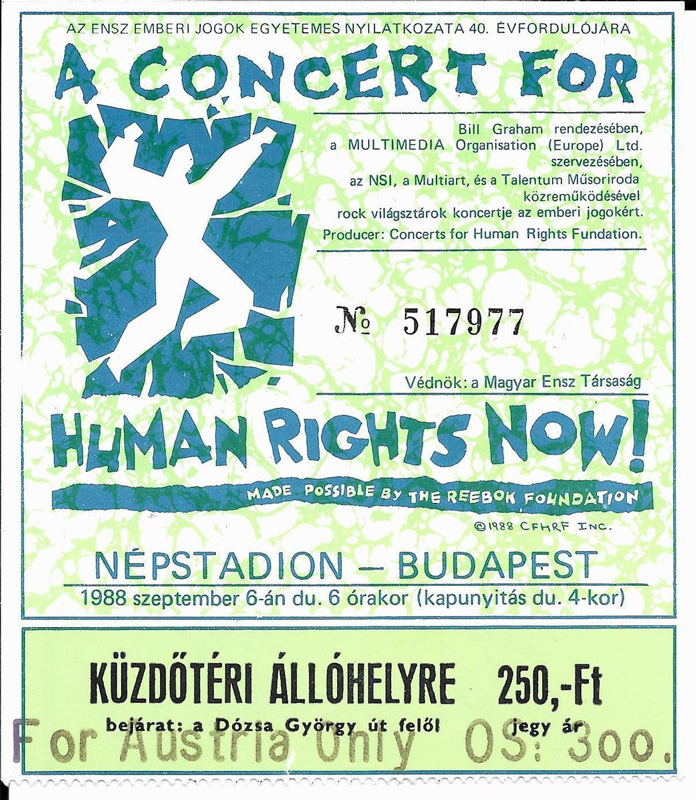

In July 1990, a year before his death in a helicopter accident, Graham travels again to the city of his birth. In 1987 he put on a rock concert in Moscow. Now he and his two sons attend Roger Waters’ “The Wall” spectacle in Berlin, which is still divided. “I realized that meant a lot to him,” recalls son Alex. “As usual, he didn’t utter anything that resonated with the traumatic part of his life. But the four or five days that we spent in Berlin he was unusually stoic and reserved.”

In July 1990, a year before his death in a helicopter accident, Graham travels again to the city of his birth. In 1987 he put on a rock concert in Moscow. Now he and his two sons attend Roger Waters’ “The Wall” spectacle in Berlin, which is still divided. “I realized that meant a lot to him,” recalls son Alex. “As usual, he didn’t utter anything that resonated with the traumatic part of his life. But the four or five days that we spent in Berlin he was unusually stoic and reserved.”

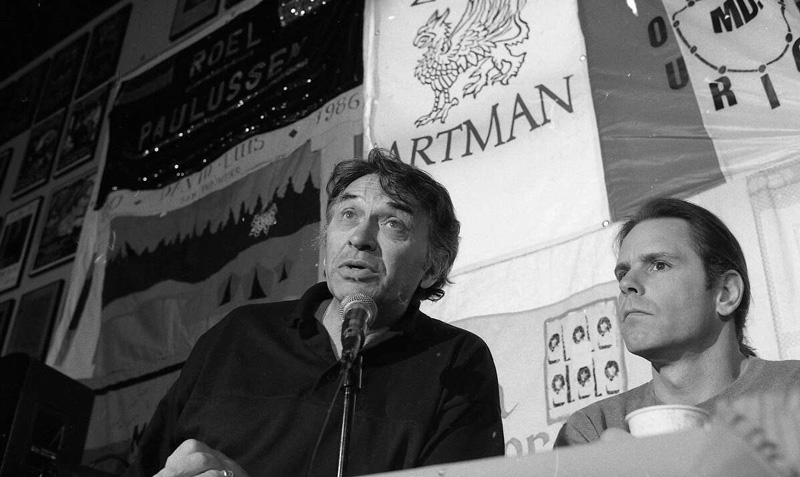

Along with more than 300,000 in the Potsdamer Platz, he experiences such people as Roger Waters, Joni Mitchell, Van Morrison, the Scorpions and the East Berlin Radio Choir marking the end of the Cold War. In the same place, Bill Graham had boarded the train 51 years earlier.